Two Point Oh: Randomness

Let's talk about random numbers and how we'll make them happen in Ethereum 2.0. What is RANDAO? What is VDF? How do they go together?

This post is part of the Two Point Oh series of Ethereum 2.0 explainers. It is recommended you read the previous installments before continuing. If you find any inaccuracies in this post, or just want to contribute in any way, please consider taking a look at The Explainers.

How does the beacon chain decide which validators' turn it is to propose a block, and which validators should attest to that proposal? How does it juggle this decision between 1024 shards and the dozens of thousands of validators active in the system at any given time?

It needs randomness.

A computer cannot generate true random numbers.

You can look at it this way: a computer is a machine which, given the same input always generates the same output. They are calculation machines, and much like a calculator cannot produce 5 for a sum of 2 and 2 (unless it's a prank or terribly broken), so too can a computer never have unrepeatable output for the same input.

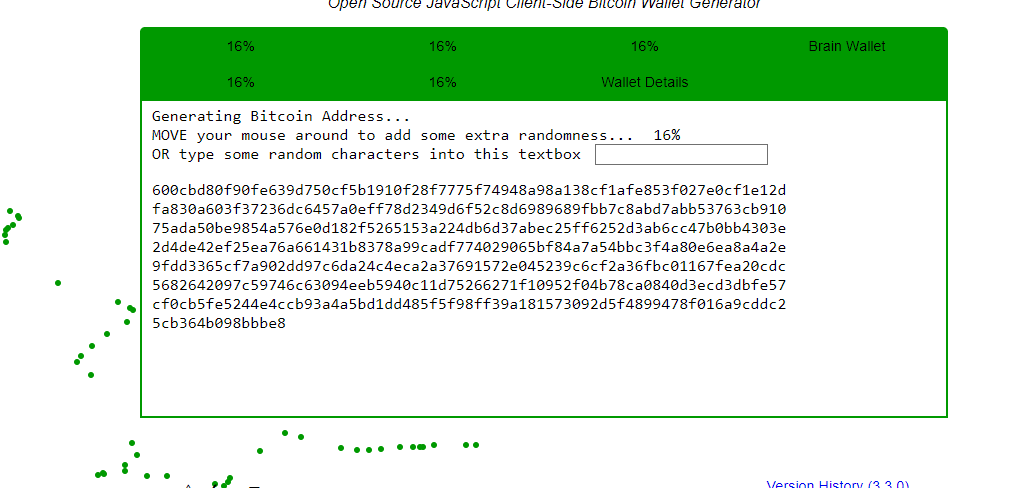

In order to generate a reasonably random number, a computer will rely on a seed: the starting point from which to do calculations, the input to its output. On top of that seed - which can be anything from the movements of the mouse cursor on the screen to all the content of Wikipedia's database - it will perform mathematical operations that eventually lead to a number that wasn't predictable to a human. Even now, if you go to BitAddress, you'll notice the "seed" change as you move your mouse. It's "collecting randomness" from your erratic movements.

How can we call this random if we're generating the seed and the same math is always applied to this seed? The thing is, when enough hard-to-repeat seeds are put together, the resulting number is reasonably random. It is impossible for a human to repeat the exact same mouse movement pattern over an area of 5 million pixels, so this is somewhat reliable. Sprinkle in some other values like time of day, positions of lava in a hundred lava lamps like CloudFlare does, and maybe the number of times a sport's team scored a goal that year, and you get a reasonably random seed.

But there's no mouse, sensor, or sports results oracle in the blockchain. What's more - even if one node arrives to a certain random number, that number MUST be the same as those of all other nodes of the blockchain, otherwise the chain will split. Different values at the same block in the same blockchain result in a fork. So how do blockchains deal with randomness?

Some rely on the block hash. Because this value is unknown and random but identical across all nodes, it is okay as a source of randomness for basic provably fair gambling.

However, if the block reward (currently 2 eth) is less than what a miner might gain by manipulating the blockhash, then it's economically rational for them to misbehave. What's more, in a Proof of Stake system where producing a block requires almost no computation time or power, a miner could easily keep generating thousands of blocks until they get a hash they like, and then submit that one.

This also applies to validator selection. If the validator currently in charge of producing a block can manipulate it in such a way that the blockhash becomes a seed which will again select them or one of their other validator clients as the proposing validator, that validator can hoard the proposal queue and keep proposing, locking others out of major profits.

Obviously, stronger blockchain randomness is needed, especially for Ethereum 2.0.

Imagine if you had a room of people. Each person imagines a number in their head. To get a random number, we ask the people, one by one, to voice their number out loud. The sum of all those numbers is our random number.

That's essentially what RANDAO is. A scheme in which, when depositing 32 ether to become a validator, a user will select a random number of their choosing. When it's time to reveal the numbers for a block, all these numbers put together will form the new random number in the system.

Note: The above process is simplified, there's layered hashing going on which we won't go into in this post - let me know on Twitter if a dedicated post about that aspect of Eth 2.0 RANDAO is desired.

But even in this case, the last to reveal has a degree of influence on the number. They can sway it one way or another by choosing to stay silent. The last person in the room will have followed along with everyone's number reveals and will know the result with or without their number. If one number is better for them than the other, they have incentive to exert that degree of manipulation, however minor.

Ethereum 2.0 will be getting around that issue with a VDF.

VDF stands for Verifiable Delay Function.

This is a fancy way of saying it takes a long time to calculate something.

If we have a number X, then for example a six-fold quadratic VDF of that X can be: ((((((X^2)^2)^2)^2)^2)^2)^2, where we square the number and that result on each of the 6 layers. So in this case, the final result of X = 5 would be

((((((5^2)^2)^2)^2)^2)^2)^2 =

(((((25^2)^2)^2)^2)^2)^2 =

((((625^2)^2)^2)^2)^2 =

(((390625^2)^2)^2)^2 =

((152587890625^2)^2)^2 =

(23283064365386962890625^2)^2 =

542101086242752217003726400434970855712890625^2 =

293873587705571876992184134305561419454666389193021880377187926569604314863681793212890625

As we go deeper, the results get more absurdly large. A reasonably deep VDF would take a long time to calculate as the math gets pretty intense for any computer. This example was inspired by an actual VDF that's up until recently been a part of a cryptographic puzzle for opening a time-capsule at MIT - it used a depth od 80 trillion squares.

So what's the point of this?

First, the delay in calculating the final number is verifiable because we know what computer operations are necessary to reach the result and can with a reasonable degree of accuracy determine how long it'll take for a machine to arrive at the result.

Second, in order to reach, for example, the third level, the computer calculating this number must have reached the second and first levels first - there is no way to do this calculation in parallel with multiple computers, because each new input depends on the previous output, and each output takes a predetermined amount of time to be calculated.

If we now feed the aforementioned random number from RANDAO into the VDF (in place of X), and if we make it a few thousand layers rather than 6, and use something other than simple squaring (^2), we end up with a function that turns the RANDAO result into something else entirely that takes a while to calculate no matter how many computers you throw at it.

By introducing this delay and by making it longer than the time window in which a validator could benefit from influencing a random number, we get rid of the final level of randomness bias - that last bit of influence a validator could have on the RANDAO generation.

In Ethereum 2.0, this VDF has been defined to be 102 minutes long - over an hour and a half. The Ethereum Foundation in tandem with Filecoin and some other blockchain projects is financing the development of an open source ASIC optimized for this calculation - a micro-computer specialized for doing this and only this calculation. The machine will be run by enthusiasts, crypto projects, other blockchains and even validators for a small advantage in being first to respond to a VDF check, and shouldn't cost more in electricity than a typical micro-computer full node.

Such a highly specialized machine makes sure that anyone else who attempts to develop a better ASIC to regain that final bit of influence has to make it 100 times more efficient for it to be effective. Developing this device would be financial suicide, barring some manner of high-profile exploit that would in all likelihood completely destroy Ethereum as we know it were it to be successful.

One epoch in Ethereum 2.0 is 6.4 minutes. One RANDAO reveal happens every epoch, which means we can run a new VDF for every epoch. This comes down to 16 VDFs - and thereby 16 random numbers - per VDF period of 102.4 minutes. This randomness is then the seed from which the next set of validators is selected, guaranteeing fairness.

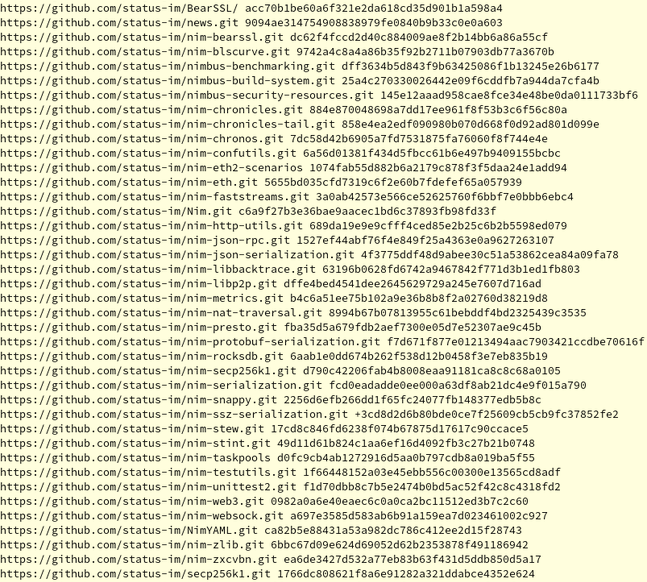

In Nimbus, we're in line with the spec. Our RANDAO implementation is complete for the 0.5.1 version of the Ethereum 2.0 specification. We need to make sure our tests match the official ones but apart from that we're good to go.

Now, it's too soon to talk about VDF. VDF is still in the research phase and once it's added to the spec, it'll take a while for clients to catch up. Methods of talking to remote VDF devices will have to be devised, staking rewards modified slightly to lean towards the block producers who also run VDFs, and so on. Right now, given that RANDAO is random enough for the blockchain's early needs, it'll do as the base layer for shuffling validators and other randomness.

We'll update this section as our implementation progresses.

Ethereum 2.0 will have a reasonably random number generated every 6.4 minutes, and this number can be considered random enough to secure immense amounts of value.

The VDF system can only fail if someone generates a VDF ASIC that's 100x more efficient than any the Ethereum community puts out or if all the VDF ASICs in the world go offline. Even if this does happen, the RANDAO security underneath it is secure to the point of minimal influence, such that it is still enough to secure the world's wealth, but maybe not the universe's wealth.